Abstracts:

The Museum of English Rural Life (The MERL) at Reading University has a significant collection of 22 English farm wagons. A “Shoulder to the Wheel” exhibition developed in partnership with the Crafts Study Centre, University for the Creative Arts, Farnham, seeks to explore the skills of the wheelwright. Using a wheel collected by the Museum which dates back to c1894 as inspiration, three contemporary makers used their different skills to create a new wheel in its image. The exhibition was guest curated by Dr Glenn Adamson, Senior Scholar at the Yale Center for British Art and runs from January – April 2020.

Le Museum of English Rural Life (The MERL) de l’Université de Reading possède une importante collection de 22 véhicules à deux ou à quatre roues. Une exposition « Shoulder to the Wheel » développée en partenariat avec le Crafts Study Centre de l’Université des arts créatifs de Farnham cherche à explorer les compétences du charron. À l’aide d’une roue recueillie par le Musée qui remonte à c1894, trois fabricants contemporains ont utilisé leurs différentes compétences pour créer une nouvelle roue à son image. L’exposition a été organisée par le commissaire invité, Dr Glenn Adamson, Senior Scholar au Yale Center for British Art et se déroule de janvier à avril 2020.

Keywords:

Exhibition practice – wheels – reconstruction – cart – carriage – wagon

The Museum of English Rural Life (The MERL), at the University of Reading, has collected evidence of traditional rural crafts from its earliest days in the 1950s. Amongst the most impressive elements of the object collection is the group of 22 English farm wagons, 4 carts and a timber carriage. Together they inspired the reference work, “The English Farm Wagon” written in 1961 by a past assistant keeper, J Geraint Jenkins. As part of the redisplay of The MERL’s collection in 2016 they were moved into a bespoke “Wagon Walk”. In January 2020 this space will be used to host an intervention and exploration of the work of the wheelwright called, Shoulder to the Wheel.

There is no point, the old adage goes, in reinventing the wheel. Whoever first said that must not have met a wheelwright. The four wheel components; hub, spokes, felloes and rim, have been constantly refined over centuries.

Shoulder to the Wheel is a collaborative exhibition between the Crafts Study Centre in Farnham, Surrey and The MERL curated by Dr Glenn Adamson, Senior Scholar at the Yale Centre for British Art.

To create the exhibition we selected a late Victorian wheel collected by The MERL in the 1960s. Three contemporary makers were then invited to create a work in its image.

Greg Rowland is the latest in a long lineage of Devon wheelwrights, dating back to the fourteenth century.

Gareth Neal is a designer and maker who often refers to old furniture in his work.

Zoe Laughlin is Co-Director of the Institute of Making at University College London, a materials library and laboratory.

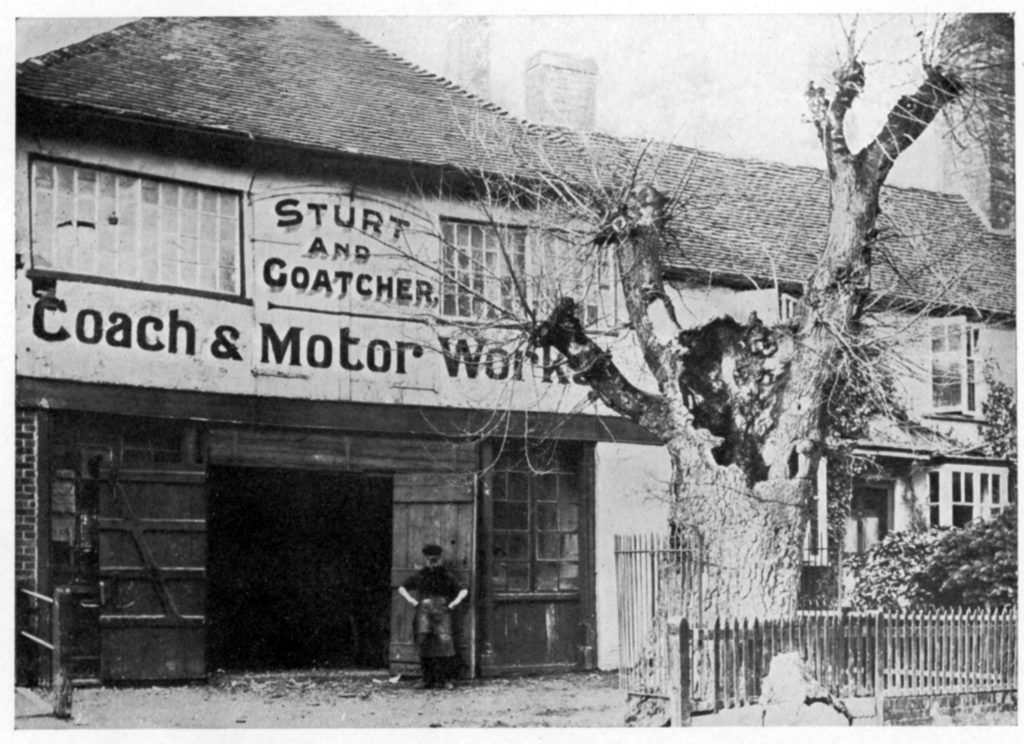

The exhibition was inspired by the work by George Sturt, The Wheelwright’s Shop, first published in 1923. His shop was located in Farnham, the home of the Crafts Study Centre.

This wheel came into the object collection of The Museum of English Rural Life in 1962, along with a West Country “ship wagon”. Both were made in 1894, by artisan C. Bailey of the village of Combe St Nicholas, Somerset, for Lords Leaze Farm, located in the nearby town of Chard. When fully loaded the wagon could carry 1,100 sheaves of wheat.

As part of the commission, each of the contemporary makers participated in a discussion about the choices they made in the design and construction of their wheel.

“Wheels are what I do and what I have done for 30 years…My aim was to use as many processes that might have been used in Sturt’s shop but also to use some modern methods not available then.

A contact near Farnham had some elm for the hub. I had to make wedges and use putty to fill the splits in the wood.

My father, Mike, produced the spokes from oak. Traditionally spokes were cleft out of the wood but we used a more modern sawing technique using air-dried stock.

The felloes – the curved pieces that make up the wheel rim, are from ash. This gave us the traditional wheel timbers of oak, ash and elm.

The iron hub rings were shrunk on. We used traditional whalebone to get the front angle of the spokes, which would form the wheel’s dish.”

How could you possibly improve the wooden wheel? It is the result of an accumulation of knowledge and experience over centuries by wheelwrights who spent their whole lives mastering the craft.

Let’s start at the beginning, then. We can picture hundreds of men dragging huge stones across a plain…Wherever they are, they are wondering how they can make this transportation more efficient.

“My wheel and its accompanying drawings are an encyclopaedia of this evolution, from the problems of drying and splitting timber, through the first attempt to make a spindle, to a celebration of the cross directional strength of the elm hub. Each thought is a step along the road that led to the wheel we know now.”

“There is often a misconception that using digital tools allows the maker, intent on copying a form with exactitude, an easy route to high fidelity results.

My first step was to scan the original wheel with a handheld infrared Asus Xtion camera attached to a laptop. No matter how slowly I swept the sensor over and around the subject, areas inexplicably failed to register.

The wheel needed to stand unaided in order to be captured in one continuous scan. I constructed a relatively unobtrusive jig of floor chocks and a thin wooden shaft leading up to the central hub of the wheel.

I decided to print the wheel with a diameter of 10cm in order to play to the strengths of the tool and ensure best print possible. I used an Ultimaker2 3D printer that extrudes polylactide (PLA) thermostat filament.

The proprietary software performs a number of adjustments in order to render a scan fit to print. In this case, an array of support structures were added to the wheel’s typology in order to compensate for areas with undercuts and gaps.

I chose to use a pink low-density polyurethane foam as my material stock from which to mill the digital ruin of a wheel. It is a material beloved of model makers in industries such as architecture, aerospace, film and Formula 1…It is lurid, smelly, relatively fragile, totally inappropriate for wheelmaking; and perfect for machinery with a CNC mill.”

All the wheels are now on display at the exhibition which opened just recently on January 14th 2020.

Isabel Hughes

Associate Director (& Head of Curatorial and Public Engagement)

Museum of English Rural Life