Abstracts

Slovenia is home to excellent beekeepers and the indigenous Carniolan bee. Beekeeping is one of the oldest traditional activities and an important part of Slovenia’s identity, natural and cultural heritage. It is a kind of a national hobby; there are 5 beekeepers per 1000 inhabitants in a population of just two million, together around 11.000. The Slovenian landscape is adorned by nearly 14,000 apiaries, containing around 200,000 hives with bees that collect quality honey and other products.

Slowenien ist die Heimat exzellenter Imker und der einheimischen Kärntner Biene. Imkerei ist eine der ältesten traditionellen Kulturpraktiken und wichtiger Teil slowenischer Identität sowie des natürlichen und kulturellen Erbes. Es ist eine Art nationales Hobby; es gibt 5 Imker pro tausend Einwohner bei einer Bevölkerung on gerade mal zwei Millionen; zusamengenommen also etwa 11.000. Die slowenische Landschaft ist geschmückt durch annähernd 14.000 Bienenstände, die etwa 200.000 Beuten enthalten und deren Bienen Qualitätshonig und andere Produkte produzieren.

Slovenija je domovina odličnih čebelarjev in avtohtone krajnske čebele. Čebelarjenje je eno najstarejših tradicionalnih dejavnosti in s tem pomemben del slovenske identitete ter naravne in kulturne dediščine. Lahko bi rekli, da je čebelarjenje nacionalni hobi, saj imamo v le dvomilijonski državi kar 5 čebelarjev na 1000 prebivalcev, skupaj jih je okoli 11.000. Slovensko pokrajino bogati skoraj 14.000 čebelnjakov z okoli 200.000 panjev s čebelami, ki nabirajo kakovosten med in druge pridelke.

Keywords

Beekeeping – Carniolan bee – bee hives – urban beekeeping – transporting bees

Beekeeping in the 18th and 19th centuries was marked by outstanding figures

Successful beekeeping has always been based on thorough knowledge of bees, ingenious beekeeping techniques, dictated by the local foraging conditions, and especially on the Carniolan bee and its excellent characteristics. Of key importance to the progress of beekeeping were several figures, who with an enthusiasm based on great human qualities taught sensible beekeeping to simple peasants, and at the same time spread their knowledge about the Carniolan bee and beekeeping to the wider world.

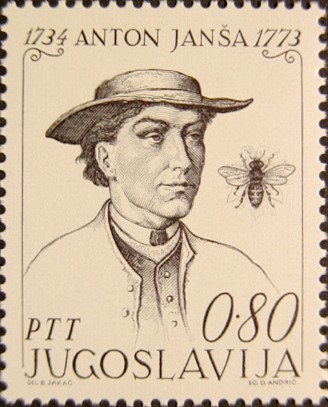

The most outstanding among them was Anton Janša (1734 – 1773), an excellent beekeeping theoretician and practitioner, and the first teacher of the subject at the Beekeeping School in Vienna. His birthday, May 20, was chosen as World Bee Day from 2018 onwards on the initiative of Slovenia.

Another figure highly important for the development of Slovenian beekeeping was the priest Peter Pavel Glavar (1721 – 1784), the founder of the first beekeeping school in Slovenia. He was among the first to write a treatise on bees in Slovene.

The Tyrolean natural scientist and physician Joannes Antonius Scopoli (1723 – 1788) was active in the Slovene territory and was the first to inform the world that the queen bee mates with drones outside the beehive.

The great beekeeping expert and first Carniolan bee trader Emil Rothschütz (1836 – 1909) was instrumental to promoting the Carniolan bee.

The pride of Slovenia – the Carniolan bee

The Carniolan bee, Apis mellifera carnica, is a Slovene indigenous bee species that originated in the area of the Balkan Peninsula, and for historical reasons, its homeland is held to be Slovenia. The species also lives in Carinthia and Styria in Austria, in Hungary, Romania, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as in Serbia; it has been artificially introduced in Germany and in many other places. Following the Italian bee, the Carniolan bee is the second most common bee species in the world.

The Carniolan bee has excellent characteristics: it is gentle, industrious, and long-lived, does not stray into other beehives, overwinters well, consumes little stored food, multiplies quickly in spring, efficiently builds combs, thoroughly exploits rich pastures, especially forest ones, has a well-developed cleaning instinct, making it less susceptible to diseases, and is very good at orientation and swarming.

Why do the Slovenes keep their bees in hives grouped in apiaries?

The principal reason for this method of beekeeping are the AŽ-hives (AŽ stands for Alberti-Žnideršič). Slovenes are very attached to their bees and make sure that they dwell in dry, warm hives, protected against the cold, heat, and bad weather by the apiary’s shelter. Apiaries differ from one region to another and Slovenes are most proud of the Slovene Apiary which has preserved its typical form for centuries. It derives from Central Slovenia and was described by Anton Janša in his book Popolni nauk za vse čebelarje (The Perfect Theory of Beekeeping) in 1772. These apiaries were mostly built by self-taught craftsmen, based on knowledge passed on by their ancestors and enriched with their own experiences, discoveries, and creativity.

The traditional Slovene beehive is thus an AŽ leaf hive. Beekeepers claim that it is the beehive best suited to our climate and foraging conditions. It was introduced by Anton Žnideršič in the early 20th century and is by far the most popular type of beehive, since over 90% of all beekeepers use one of its variants. It is also spreading elsewhere around the world. The AŽ-beehive is very handy for transporting bees to different pastures, as well.

Painted beehive panels are a specific Slovene phenomenon

The painted front panels of the formerly plain kranjič hives are part of Slovene cultural heritage that almost every Slovene is familiar with. They are a genuinely original Slovene cultural element. After emerging as a genre of folk art, largely created by and for members of the peasant classes, in a part of the Slovene ethnic territory in the mid-18th century, the custom peaked between 1820 and 1880, to decline due to socio-economic and religious conditions in the early 20th century.

Beekeeping in towns

Urban beekeeping is not something new or exceptional in our towns, but the practice has recently seen a revival around the world, including in Slovenia. The bees can produce quality and above all pristine honey in our towns, since there are no areas affected by phytopharmaceutical products. Apiaries, but more often stands of box hives, are set up on the roofs of commercial buildings, on balconies, or in gardens.

Beekeeping is above all a relaxation activity for townspeople. It provides them with bee products and contact with nature close to their home, contributing to their well-being and a quality “green way of living”.

Transporting bees to pastures

Transporting bees from places with poor pastures to better ones, especially forest pastures, is a centuries-old tradition in Slovenia, which also spread elsewhere in the late 18th century thanks to Anton Janša.

There are indeed no places in Slovenia that would provide enough pasture for an entire beekeeping season. Transporting bees is above all of economic importance, as it allows beekeepers to exploit the honeydew produced by some insects on plants at different times and in different places. The practice requires special knowledge and skills and these are continuously being improved.

Bees and bee products have a beneficial effect on people

Beekeepers increasingly adapt their apiaries into apitherapy rooms, where people can inhale the healing aromatic air produced by the hives. Apiaries are thus no longer merely small or large structures protecting bees, but have been turned into refuges for the well-being of body and mind. Bee products like honey, propolis (bee glue), pollen, wax, and royal jelly have a beneficial effect on health, while apitherapy with bee-venom seems to be effective in treating rheumatoid arthritis and other diseases.

Barbara Sosič, Slovene Ethnographic Museum, Ljubljana

Thank you, AIMA and Claus Kropp, for this excellent piece on bees…which I’m sharing with members of our local beekeepers association, as well as the beekeepers at Howell Living History Farm in Hopewell Township, New Jersey. The section on transportation of bees will be of special interest, given New Jersey’s history as “The Garden State” and the use of shipped-in bees on many farms and orchards, in both the past and present. Today, there are increasing examples of urban beekeeping in cities like Newark, Hoboken and Trenton; also, increased public interest in backyard beekeeping. The blog will be valuable (and inspirational!) to all who have the good fortune of seeing it, including the Howell Farm educators who bring lessons about bees into classrooms of local schools through both virtual and live presentations. (BTW, we are planning to become an AIMA member so that we can bring more/better international perspectives to our programs.)