For the past 40 years or so, a “house cow” has been a valued part of our family. We have had a series of seven cows of different breeds, including two Jerseys, three milking shorthorns, a shorthorn/ Holstein cross, and our current cow: a Jersey/ brown Swiss cross.

Thanks to these marvelous animals, our family has had access to a lot of milk, much more than what was needed to raise the cows’ calves. Over the years the plentiful milk and the desire to not waste it has led us into learning a lot about home dairy processing, both by “trial and error” (lots of that) and also by studying biochemistry. Understanding biochemistry is very helpful in making sense of dairy processing, whether you are an archeologist or a food scientist or simply an interested consumer.

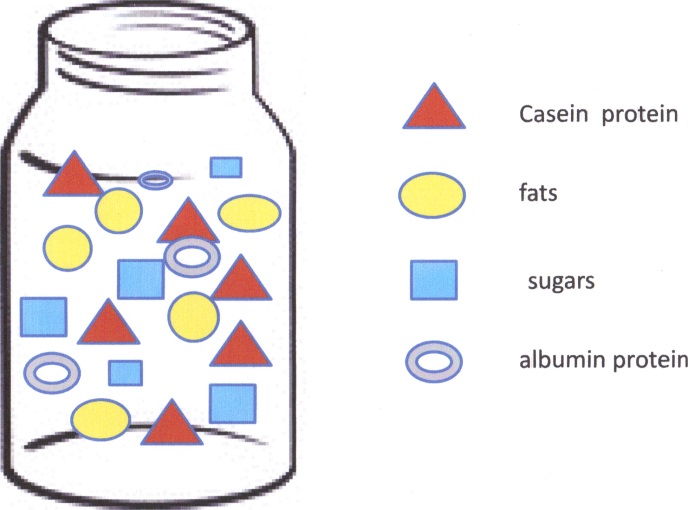

Simplified milk biochemistry:

Milk from any mammal is a solution of water mixed with proteins, sugars, fats, and other molecules like minerals and vitamins. The components of milk interact in complex ways, but for simplicity’s sake it’s useful to consider their biochemistry separately, like this:

-sugars are the basis of fermentation processes, which produce milk products like yogurt;

-fats are agitated (churned) to produce butter ;

-proteins are the basis of coagulation (curdling) which produces cheese .

Fermentation

The main sugar in milk is lactose. It is a disaccharide, and digesting it (breaking it into simple sugars) requires a specific enzyme called lactase. Infant mammals can make lactase in the cells that line the intestine, but in adult mammals the intestinal cells generally (with some exceptions) lose the ability. Certain species of microbes, on the other hand, have evolved to use lactose as their main energy source, and the ability to make lactase is one of their specialties that allows them to survive.

Once lactose is broken into its components (sucrose and galactose) microbes break down these monosaccharides further to provide energy and other products by way of a metabolic pathway called fermentation or anaerobic glycolysis.

Microbes digesting lactose in milk are the basis of fermented milk products like yogurt, kefir, koumiss, skyr, buttermilk, and sour cream. Although these products are all made by fermentation, they differ based on the source of the milk, the species of microbe(s) involved, and many other factors large and small. I have made all of the products in my list above, except koumiss, which is made from mare’s milk. Our favorite fermented milk product so far is yogurt.

This is how I make it:

I take a gallon (3.75 litres) of whole, unpasteurized milk and heat it to 190o Fahrenheit (88o Celsius), stirring it to prevent scorching. The milk should stay at 190o for 5 minutes. It’s important to heat the milk that hot and to leave it at that high temperature because you want to alter (and partially coagulate) the proteins in the milk. Heating the milk to a lower temperature and holding it for longer will pasteurize the milk, but it will not alter the proteins, and that means the finished product will be softer and more runny.

After the milk has been heated for the necessary time, I pour it, still very hot, into four clean 1- quart (0.95 litre) jars, and cap the jars. The heated milk sterilizes the jars and lids so I am able to skip sterilizing as a separate step. Then I let the jars cool to 110o – 115o F (43o – 46o C). The bacteria that produce the best yogurt (in our opinion anyway) are thermophilic, which means they do best at higher temperatures. Other cultures may require a lower temperature, e.g. 90o-105o F (32o-40o C).

Once the milk in the jars is the right temperature, I add a commercial yogurt culture that I purchase as a freeze-dried product from a cheesemaking supply company.

Of course, you can also make your own “mother culture” from the previous batch of fermented milk, but I have found that with time the culture changes, as my kitchen’s native microflora replaces some of the species in the commercial culture. The changes in the culture mean that the yogurt is different too. The results of my “homemade” culture have certainly been edible, but we prefer the results of the commercial culture.

After adding the culture and stirring gently, cap the jars again and incubate them for 6 – 12 hours. The longer it incubates, the more tart the final product will be, assuming the temperature is stable. There are many ways to incubate the milk, including electronic equipment, but I use an insulated box just big enough to hold the jars. In summer the container itself is enough, and in winter, I wrap the container in blankets or newspaper to keep the contents warm longer.

Author: Barbara Corson, veterinarian