The Crèvecoeur chicken is among the oldest of the standard-bred fowls of France and the longest known French breed in the United Kingdom. The breed gets its name from the village of Crèvecœur en Auge in Normandy, France. “Crève Cœur” translates literally as “broken heart.”

Editor’s Note: Jeannette is a connaisseur of the Crèvecoeur chicken and this is an on-going contribution to her exploration of their history. Also see the earlier episodes in this delightful saga in AIMA Newsletter N°10: and AIMA Newsletter N° 13 Part 1:

Local history cites the origin of the name as stemming from the land in this region being less fertile than was hoped by farmers moving in to the area and thus breaking the hearts of the peasants. Little is known of the breed’s origins other than they were developed in Normandy and existed there for a very long time.

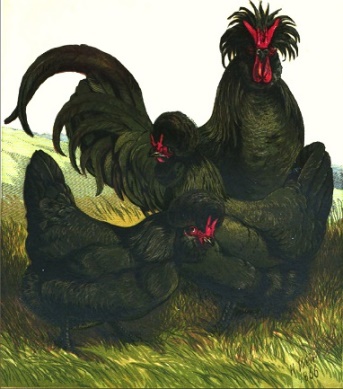

By the eighteenth century, Crèvecœur capon was a preferred meat of the upper middle class in Paris. More than 150,000 were produced for this market annually. French poultry author Charles Jacque wrote in his 1858 book, Le Poulailler, “This admirable race produces certainly the most excellent fowls that appear in the markets of France. Its bones are even lighter than those of the Houdan; its flesh is fine, short, whiter, and it takes more easily to the fattening process.” Illustration from The Poultry Book 1867.

Aside from its culinary accolades, the Crèvecœur came to play an unwitting part of early aviation history. According to the British Balloon Museum and Library, on September 19th, 1883 Etienne Montgolfier built the balloon he called the Aérostat Réveillon (“Réveillon Balloon”). Because of the unknown dangers of flight, the balloon was “manned” by the first living beings to fly in an untethered balloon flight – a Berichon sheep named Montauciel (“Climb-to-the-sky”), a Challans duck, and a Crèvecœur cockerel. Human passengers would follow soon after that same year.

The animals’ flight took off from the grounds of la Folie Titon near the house in Paris belonging to Etienne’s friend, Jean-Baptiste Réveillon. The flight only lasted about 15 minutes before the balloon came to the ground. All three animal passengers survived to become a little known part of aviation history.

Another notable distinction for the Crèvecœur occurred in 1889 when there were two sets of awards offered for poultry at the first Exhibition Universelle (World’s Fair) held in Paris. One was reserved for the Crèvecœur and the other for all the other chicken breeds at the exposition. The dominance of the breed in French poultry exhibition continued toward the 20th century. In 1891, The Journal de L’Agriculture reported on that year’s annual agricultural competition held in Paris. A poultry journalist at the show remarked in his article on the Crèvecœur that “It was she who was deemed worthy of the aviary of honor.”

The Crèvecœur remained popular up until the early 20th century in France. Poultry author Willis Grant Johnson wrote in 1909 “When staying in St. Servan, Dinan, and St. Malo a few years since, I noticed that the Crèvecœur was the principal fowl offered for sale in the market, where they were mostly bought alive, and if unsold carried home, to possibly reappear on a future day.”

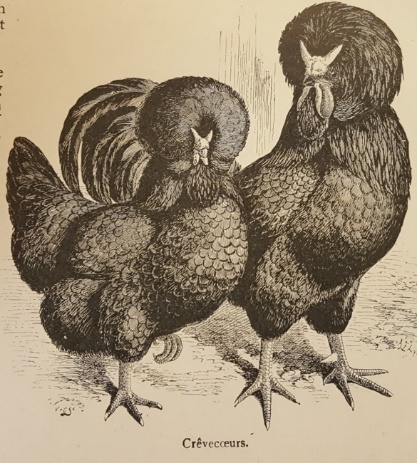

He also mentions in regards to capons that “In Paris the finest of the “Crèves” realize as much as from twenty to twenty-five franc each, while from three to five dollars is not an uncommon price in New York. The French capon, when really good, is in its way the perfection of poultry.” (The Poultry Book, 1909). Illustration from Wrights Book of Poultry 1912.

To put things in perspective, in today’s currency, that price is equivalent to $100-$125 per bird if you had wanted one for your table!

It was about this time when Crèvecœurs may have had another brush with history. It infamously would be on the high seas aboard the Titanic. (Yes, that Titanic.) It is a known from historical accounts and records that four “fancy French fowl” were purchased by passenger Ms. Ella Holmes White from where she reported in her insurance claim was the “Jardin d’Agriculture.” Since no park of that name existed, I believe she may have confused the name making it likely she meant to say Jardin d’Acclimation. This was a fascinating park in Paris focused on producing novel plants and animals from France and all over the globe. The animals and plants were “acclimatized” to the local land and climate and then judged to see if they would be useful for agriculture. The facility then sold the useful plants and animals to the public. It is well documented that among the domestic animals produced at Jardin d’Acclimatation were Crèvecœurs as mentioned in this article from American Stock Journal in 1870.

Ms. Holmes boarded the Titanic in Cherbourg along with her best friend Marie Grice Young. It was Marie who took care of the two roosters and two hens who were secured below decks in stowage. Ella and Marie ultimately survived the sinking of the ship but, alas, the fancy French fowl did not. There are several accounts of passengers hearing the roosters crowing through the walls of stowage as the ship went down.

Ella eventually made her way home and soon filed an insurance claim for $207.87 with White Star Lines. This is the sum she claimed she had paid for her lost birds. In today’s dollars that would be over $6500.00 which is a mighty sum for four chickens!

The search for more evidence on the Titanic’s ill-fated chickens continues and I welcome anyone that would like to join in the sleuthing. Based on the evidence we have thus far, I’d put my money on the Crèvecœur. There were few birds in France at the time with the notoriety, reputation as a table bird, and who commanded the same price of Crèvecœur fowl.

Sadly, the breed was nearly wiped out in France during WWII. Numbers never recovered and today the Crèvecœur is considered critically endangered. Few exist in France but there is a farmer’s movement in Normandy to bring them back from the edge of extinction.

In the United States, the Crèvecœur has remained since 1852 when the first imports were made. This population is also considered at risk of extinction but numbers have grown considerably in the past 10 years. There is an American resurgence in interest for the breed as exhibition fowl. More importantly, the birds are finding their way back to the tables of discerning epicureans who are lucky enough to experience the culinary delight of having a Crèvecœur for dinner.

Also see the British Balloon Museum story: The day a duck a sheep and a cockerel took to the air in 1783

PS from Jeannette: Here are images of the Challans duck breed and the Berrichon sheep. There are actually two types of Berrichon sheep, the Berrichon du Cher and the Berrichon de l’Indre. The Cher is the older of the two and would have been around at the time of the balloon flight. The Berrichon de l’Indre was created in the late 1800’s.

Author: Jeannette Beranger, Project Manager, The Livestock Conservancy