Hyperinflation – based on the original handwritten budget book in German by Xaver Haslinger.

Author: Albert Kühnstetter (ÖLM) with the support of Hans Ziegler.

Preliminary remarks

About two years ago I was approached by Hans Ziegler, a farmer and friend from the Rotthalmünster area in Lower Bavaria. It was triggered by the discussion about inflation, which was flaring up again at the time. He had found his wife’s grandfather’s detailed budget book from the 1920s. A time that was characterised by hyperinflation in Germany, especially in the first half of the decade.

He gave me the records, some additional information and photos on the history of the estate with the suggestion to write an article on the subject of the hyperinflation of 1923 using the history of his farm as an example.

Inflation was one of the few foreign words that my great aunt, who lived in our house during my childhood, knew. She was born in 1893 and was 30 years old at the end of 1923, so she had fond memories of the period of rapid currency devaluation. So basically, I had already learnt about the term from her stories as a child – stories that shaped generations throughout Germany and made the term inflation a non-word in our country until today.

Having been influenced by a contemporary witness, I was immediately interested when Hans Ziegler showed me the budget book from this period and suggested that I use it as the basis for an article about this time. Of course, the fact that November 2023 marks the one hundredth anniversary of the peak of inflation also played a role in the decision to write this article.

Subject of the budget book

The estate “Zum Radler” has a history dating back to the Middle Ages. It was first mentioned as “Raedler da der Hiltprant sitzet” (1) in Duke Henry the XIV’s land register (Urbar) from 1320. Duke Henry the Rich’s land register of 1435 mentions the estate again, this time under the name Rädlär.

In the tax assessment of the district court of Griesbach from 1538, an Anndre Rädler is mentioned as the owner of this fief. He had to pay his taxes to the caste in Griesbach. However, the estate was left to him as a fief with hereditary rights. The name Rädler remained on the estate until 1689. The fief was presumably divided in the 16th or 17th century, as the records from 1689 refer to ½ farm. This was followed by the surname Resch until 1752 and the name Tettenhamer from 1811 onwards. This family remained in possession of the estate “Zum Radler” until around 1900. Aloisia Tettenhamer – the last person with this surname on the estate – married a local farmer called Wimmer.

However, as their only daughter died in childhood, the farm “Zum Radler” was sold in 1900. Maria, née Riermeier and wife of Xaver Haslinger, was a distant relative of Aloisia Tettenhamer. This relationship led to the sale to Xaver and Maria Haslinger, who paid 60,000 marks for the property. This was the Xaver Haslinger who was also the author of the budget book, which is the subject of this article.

The estate had an area of 42 hectares, of which 7 hectares were woodland. The remaining 35 ha were divided equally between meadows and fields. During the period covered by the budget book, three maids worked permanently on the farm. As three of their sons usually worked on the farm, Maria and Xaver had no long-term farm labourers. When work peaked on the farm, for example during the harvest, day labourers or temporary workers were hired.

Source for this chapter (2)

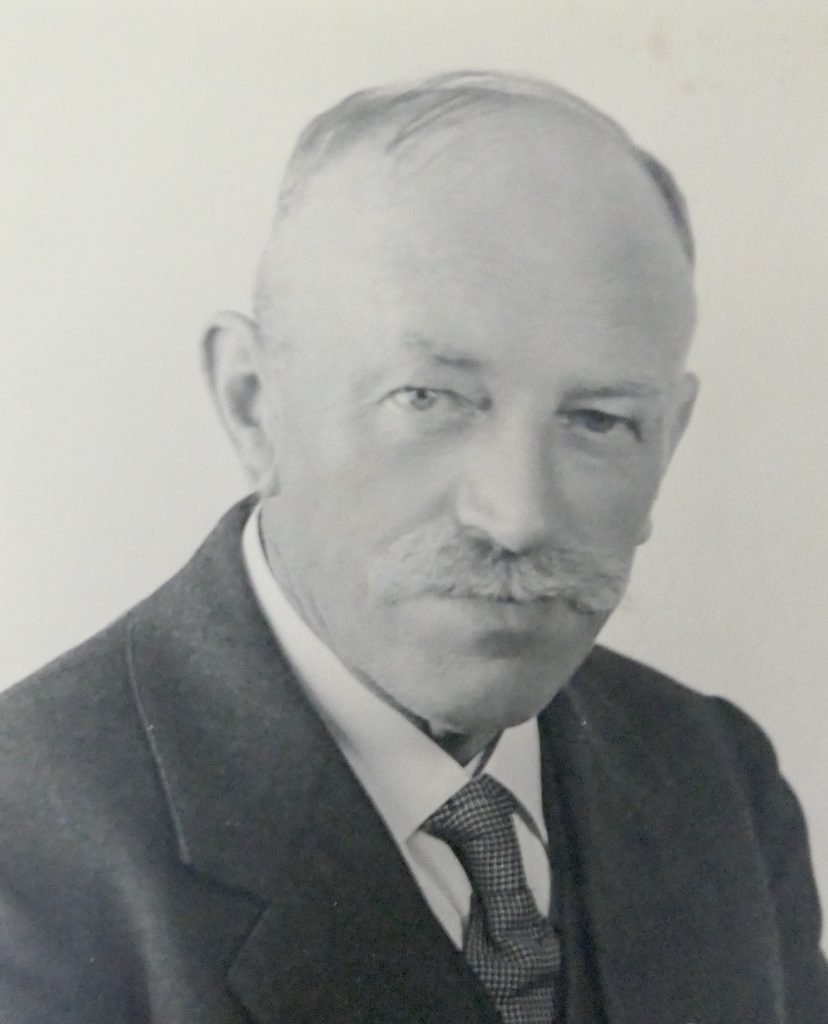

About the author of the budget book

Xaver Haslinger was born on 18/03/1874. He was married to Maria, née Riermeier, and acquired the farm “Zum Radler” together with his wife around 1900. He died on 23 February 1940 and the couple had a total of ten children, three daughters and seven sons. Three of the sons died in the Second World War. The estate “Zum Radler” was taken over by their son Johann Haslinger. Johann was married to Amalie. Their daughter Franziska married Johann Ziegler, who gave me the budget book to create this article. (2)

The records show that Xaver Haslinger was also mayor of Weimörting, at least at the beginning of the records. In addition to farming, he was also active as a hunter and beekeeper.

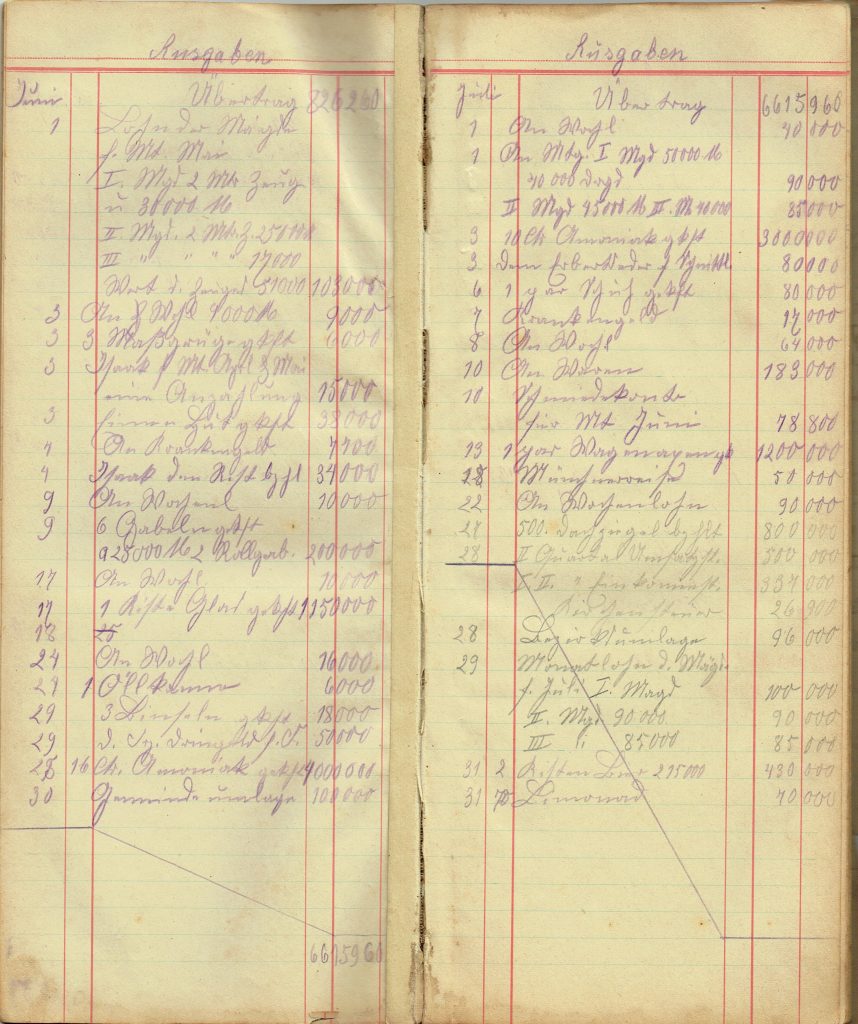

The budget book and its analysis

The budget book covers the finances of the estate “Zum Radler” from the end of 1921 to the end of 1929. It contains all the main income and expenditure for the farm and private life.

The records in German handwriting were quite difficult to decipher. With the help of Hans Ziegler, an analysable transcription was made.

Some items on the expenditure side as well as on the income side run like red threads through the entire period of the budget book. Based on these recurring items, it was possible to carry out some analyses and record trends. I have divided the items into different categories to simplify the analyses.

The expenditure categories:

- Charges – taxes and levies to the state and local authorities

- Doctor/veterinarian – medicines for animals and humans were also included here.

- Forest and Garden Trees – includes expenses for fruit trees as well as for the reforestation of the farm’s own forest.

- Feed/grain/fertiliser – seed was included here.

- Equipment/operating resources – materials and equipment required to carry out work on the farm

- Craftsmen’s services – construction services, machine thresher, blacksmith, miller, etc.

- Clothing – including expenses for tailors

- Health insurance / Health care

- Food

- Wages of servants/children – wages for residents of the estate, money given to children, as well as wages for day labourers and temporary workers

- Furniture/furnishings

- Travel/gifts

- Donations/contributions/fees – membership fees, subscriptions, etc.

- Purchase of animals for adding to farm´s own livestock

- Insurance

The income categories:

- Plant products

- Vegetables – mainly potatoes

- Cereals

- Fruit

- Animals and animal products

- Dairy products/eggs/lard

- Horses

- Cattle

- Sheep

- Pigs – including piglets that were sold

- Other income

- Capital income

- Income as mayor and other labour income

- Prize money from breeding shows

- Etc.

The sources of income mentioned above show that this is a diversified farm with various livestock and also various plant products.

Both income and expenditure categories were totaled on a monthly basis for the analysis. This made it possible to analyse trends in income and expenditure and for various individual categories.

Historical background

The basis for hyperinflation in Germany, which peaked and ended in November 1923, had already been laid shortly before the First World War and an almost continuous development followed up until November 1923. Although the Allies’ demands for reparations after the war played a major role in fueling inflation, the foundation stone was laid with the dissolution of the gold standard of the Mark on 4 August 1914. This was a reaction by the German Reich government and the Reichsbank to the hoarding of gold coins by the population, which was the population´s reaction to the uncertainties of the political developments in July 1914.

From then on, the banknote currency was backed by bonds issued by the Reich. In addition, loan offices were able to put loan notes into circulation as a means of payment. This paved the way for increased banknote printing as a means of state financing. With the war financing based on these measures, the amount of money in circulation increased fivefold between 1914 and 1918.

After the First World War, there were a number of other factors that ultimately contributed to the rapid devaluation of money.

The first factor was that the war bonds, which the German Reich had taken from its citizens to finance the war, were no longer worth anything because the war had been lost. All those who, remembering the victorious war with France in 1870/1871, had hoped for another victory and the accompanying financial blessing, including a second Founders’ Period, were now thoroughly disappointed. The capital invested in the war bonds was lost because the repayment of the state’s debts to its lenders was financed by the printing press and not by the equivalent value of a successful war.

Added to this were the increased social costs for surviving dependents and invalids as a result of the war, as well as the costs of converting from a war economy to a peacetime economy. Due to the financial policy conditions created at the beginning of the First World War, this was again financed by bonds and loan notes.

Another important contribution on the road to hyperinflation was the German Reich’s reaction to the invasion of the Ruhr region by France and Belgium, which was triggered by sluggish reparations payments. Passive resistance was proclaimed in the occupied territory. The strikers were supported by the state, which was again financed by a further acceleration of the printing presses.

Germany fell further and further into the debt trap. “The revenue from taxes, customs duties and levies was nowhere near enough to cover the financial requirements. The Reich’s debt service was 126 per cent of state revenue.” (5) As a result, the debt continued to rise.

Foreign currency purchases to settle reparation claims led to a further decline in the value of the German currency. Banknote presses were once again the means of choice for the German government to compensate the rising debts.

Until 1922, the 1000-Mark note was the largest banknote in circulation. This increased very quickly in the course of 1923 until the 100-trillion-Mark note marked the peak in November 1923. As the printing works could no longer keep up with the printing of the banknotes, emergency money was issued by local authorities, cities and even some companies.

“In total, over 700 trillion Marks (700,000,000,000,000,000,000 Marks) were issued as emergency money and around 524 trillion Marks (524,000,000,000,000,000,000 Marks) were issued by the Reichsbank.” (6)

The consequences for the population were dire. Prices for goods and services rose dramatically. The rise in wages could not compensate for these price increases. Due to the rapid decline in the value of money, more and more goods were held back and only the bare necessities were sold, as the goods retained their value, while the money released from the sale of goods lost its value after a several hours. As a result, many goods went straight into the barter trade. Farms like that of the family Haslinger were in a relatively fortunate position, as they produced a wide range of products and were therefore able to cover their own needs to a large extent from their own production.

The population’s savings, which were mostly invested in monetary assets, were no longer worth anything – large sections of the population became impoverished. On the other hand, material assets such as property also lost value as there was no longer any demand for them. Wages were often paid out daily and everyone immediately tried to exchange the money for goods. Services were often only available in exchange for goods. Prices were updated every hour.

However, there were also profiteers who were able to significantly expand their possessions by taking on debt in higher-value money and repaying it in lower-value money. These profiteers benefited from the principle “Mark = Mark” (7). “An even greater profiteer, however, was the state. Its total war debt of 164 billion marks amounted to just 16.4 Pfennigs at the time of the currency changeover on 15 November 1923.” (8)

In view of the complete devaluation of the Mark, administrative units issued stable-value emergency money in the form of vouchers for goods and material assets. These notes were denominated in everyday necessities such as grain, coal, sugar, bacon, etc. Emergency money based on gold cover was also put into circulation.

The German government had recognised that an end to the Ruhr Strike was an important step towards ending the chaos. The Stresemann government took this step on 26 September 1923, but this provoked massive protests from nationalist-minded groups. Calls for a military dictatorship were raised and Hitler wanted to exploit this situation for his putsch in Munich on 8/9 November 1923. On the other hand, the left-wing associations radicalised themselves against a possible “large-scale capitalist military dictatorship” (9). Reich President Friedrich Ebert imposed a state of emergency on the German Reich on 27 September 1923.

On 16 October, it was decided to establish the Deutsche Rentenbank. It was endowed with a share capital of 3.2 billion Rentenmarks. This share capital was covered by a land charge, which was backed by German agriculture, industry and commerce. At the time of the currency reform on 15 November 1923, the dollar exchange rate was set at 4.2 Rentenmark. This in turn corresponded to an exchange value of 1 trillion marks to one Rentenmark. As the Rentenmark notes were still insufficient at the beginning of the currency reform, some emergency bank notes remained in circulation until mid-1924.

In view of the catastrophic conditions in Germany during the inflationary period, the Allies reformed the payment plans for the reparation claims. A gold-backed bond of 800 million marks was issued to stabilise the Mark and the Reichsbank became an institution independent of the government on 30 August 1924. The Reichsmark was then introduced as the currency in October 1924.

The impact of big policy on the farm “Zum Radler”

How did these pollical events affect the farm in Lower Bavaria? As it was still common at that time, the farm that Xaver Haslinger ran in the 1920s was a farm with diverse production of both animal and plant products. The household accounts show that only a small amount of food was purchased. It can therefore be concluded that the farm was largely self-supplying. Only 2.7% of expenditure was spent on food. By comparison, the statistics on the cost of living in December 2022 show a 15% share of expenditure on food for the average German household (10). This meant that the residents of the estate were in the fortunate position of spending only a small amount of money on food – money that, at the height of the inflationary period, was barely worth anything within a very short time.

The most striking item here was only an amount of 10,440,000 Marks for 87 liters of beer, which was provided for the steam threshing crew on 18 August 1923. Beer was a basic good for Bavarians and, especially for a hardworking threshing crew, a good motivation. Examining the price for the beer for the steam threshing crew is a good indication for the “currency history” in Germany in the 1920s:

- 400 Marks were spent in October 1921 on beer for the threshing crew.

- It was then 1,469 Marks in September 1922

- In mid-August 1923, a record-breaking amount of 10,440,000 Marks was paid for 87 liters of beer

- In 1924, After the currency reform, the thresher crew members received their beer for just 20 marks.

- And in September 1925, 37.7 Marks was spent on beer for the threshing team.

The financial situation of the “Zum Radler” estate in the 1920s

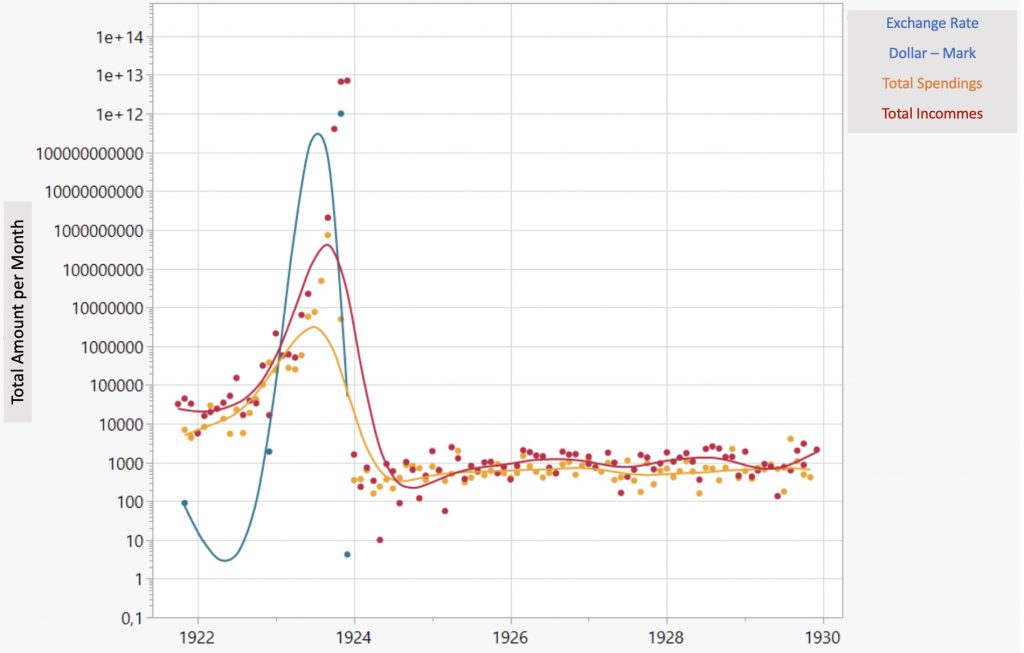

As can be seen from the reasons outlined in the historical background, a continuous increase in both income and expenditure can be seen. The monthly sums received and spent increased more than tenfold from January 1922 to December 1922 – a dramatic inflationary figure from today’s perspective. But things were to get even worse the following year. There was an almost 100-million-fold increase on the income side and “only” a 10,000-fold increase on the expenditure side from the beginning of 1923 to 15th of November 1923. This difference is due to the fact that with increasing inflation, less and less was bought for farm requirements. This fact cannot be seen in a simple analysis of the monthly totals. It requires a look at the budget book which reveals the significant reduction in the number of individual income items per month in the period from mid-1923 to mid-1924 and also for expenditure in the last quarter of 1923. If the number of income and expenditure items had remained constant over the months, the trends in the monthly totals would show the true extent of inflation more clearly.

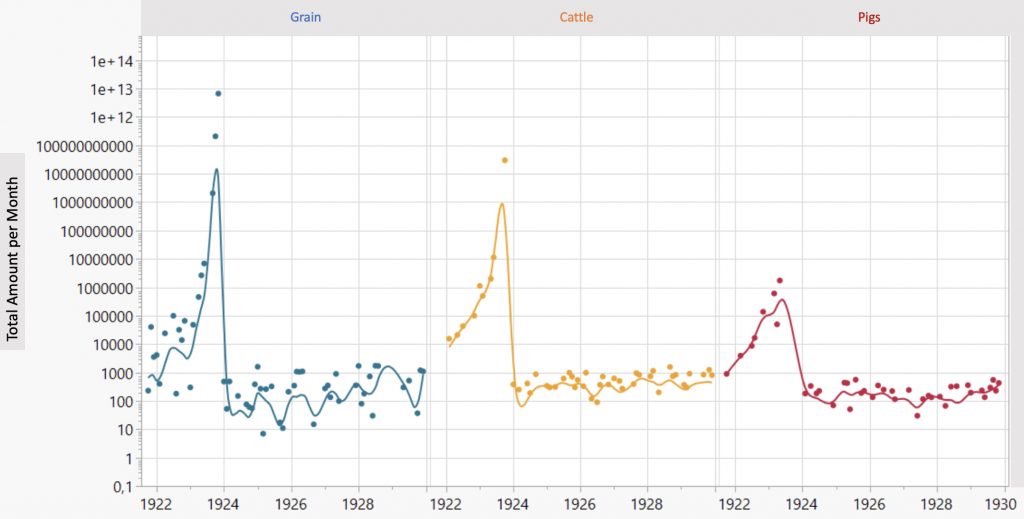

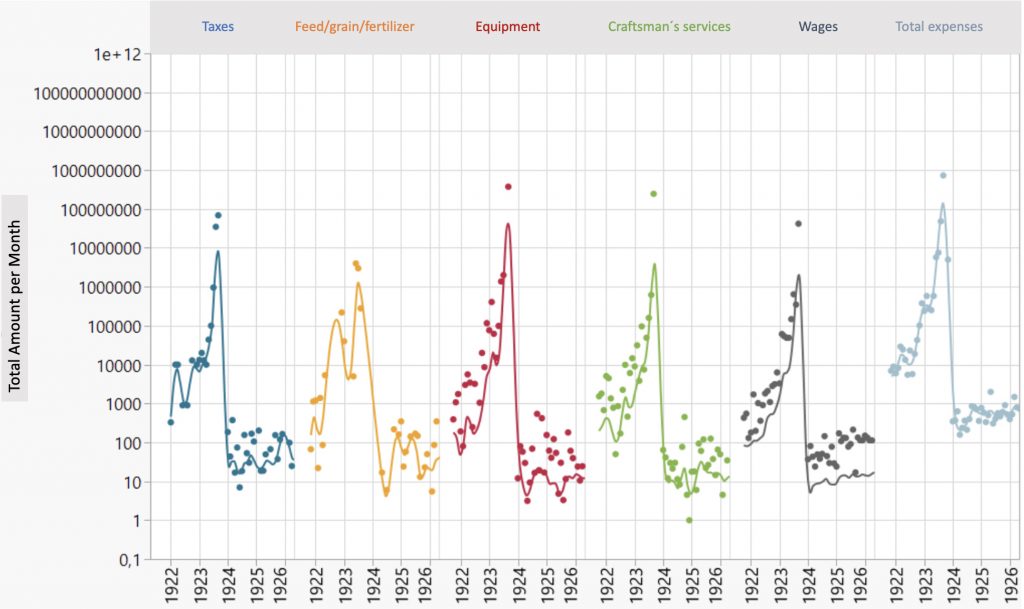

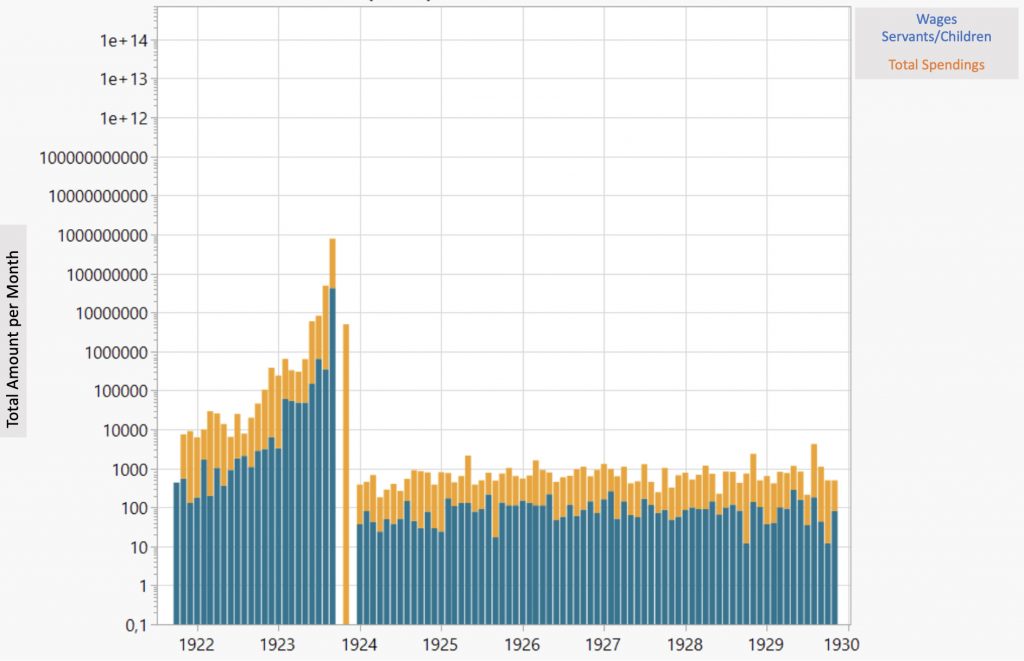

Note on the following charts: Logarithmic scaling was selected for the vertical axis in the trend graphs. This means that one graduation mark upwards represents a tenfold increase. This form of plotting was chosen so that the phases before and after the hyperinflation as well as the hyperinflation in 1923 can be clearly visualized and evaluated in comparison.

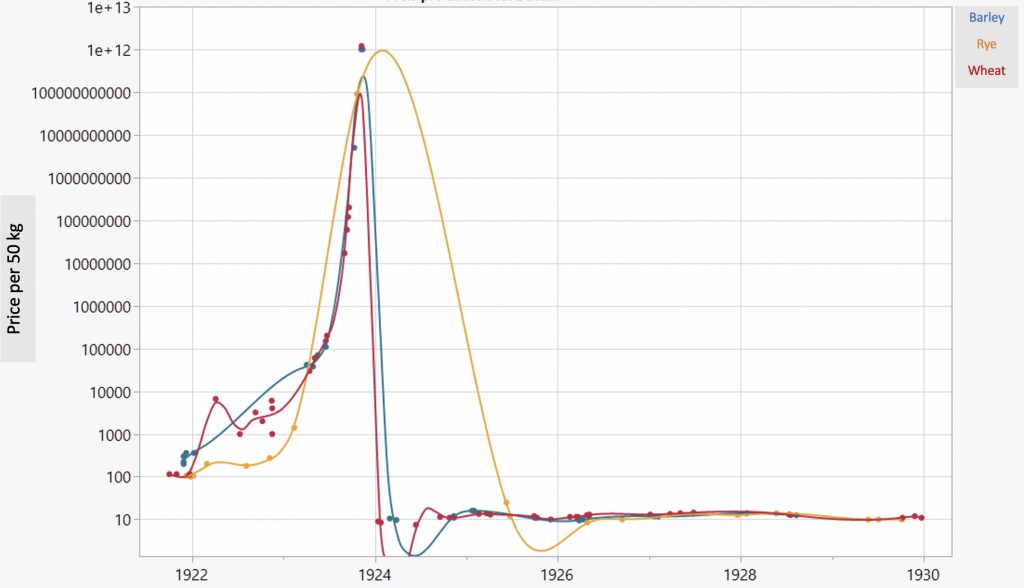

The peak of hyperinflation becomes clearer when you look at the price development per hundredweight for the different types of grain produced on the farm. Analising the price of grain was a good idea because Xaver Haslinger also sold grain during the period of hyperinflation. This analysis shows an increase in the prices realised in 1923 of at least one billion, which is an order of magnitude more than the increase in revenue. In November 1923, for example, the farm earned one trillion Marks for a hundredweight of grain. At the beginning of 1923 it was around 2000 Marks and after the currency reform it was around 10 Marks.

If you look at the development of the Dollar exchange rate in comparison, the dramatic fall in the value of the Mark becomes much clearer than when you look at the budget book, which already reflects the reaction of the farm owner to the financial situation. The exchange rate of the Dollar rose by another order of magnitude more than 10 billion times in the same period (11).

What were the owner’s reactions to the financial situation? The budget book shows increasing restraint in income and expenditure. Whether material and labour services were increasingly exchanged for farm products can only be an object of speculation as this is not shown. However, the analysis of products and animals that were regularly sold shows that Xaver Haslinger sold animals less frequently around the peak of inflation than before or after. As a diversified farm, the fodder was largely produced on the farm and did not have to be bought for money. This meant that there was no compelling reason to sell animals during the hyperinflation phase. On the other hand, there was probably hardly any demand for them. Grain, on the other hand, was also sold during hyperinflation. On the one hand, it was more difficult to store grain adequately protected from spoilage and pests on the farm. On the other hand, grain was still needed for bread production, so there was also a demand for it.

All evaluations on both the income side and the expenditure side, as well as some exemplary evaluations of individual categories, show that the financial situation for the farm had largely stabilised again from mid-1924 and remained stable until the end of 1929. However, strong monthly fluctuations can still be seen on the income side until mid-1925.

A comparison of income and expenditure over the entire period of the budget book shows that Xaver Haslinger managed his business properly. He was able to close all years with a profit. Only the year 1923 does not show a profit. In 1923, however, income was also higher than expenditure.

On the expenditure side, there are 5 major groups which together account for over 50% of all the farm´s expenditure. These are

- Taxes to the state or the municipality,

- Expenditure on animal feed, grain and fertiliser,

- equipment and resources for the house and farm,

- payments for craftsmen’s services

- and the wages of servants and day labourers, including payments to the farm’s own children working on the farm.

These 5 groups each account for around 10 to 15% of total expenditure per month. This share remained fairly stable over the period of the budget book.

With a total tax rate to the state, local authorities and church tax of approximately 11.3% of farm income, the tax rate was lower than that which agricultural businesses have to pay today. VAT alone is already at 9% today (12).

A comparison of total expenditure with expenditure on wages again clearly shows the constant share of this expenditure group over the entire period of the budget book.

Expenditure on wages increased more than 100,000-fold between the end of 1921 and mid-1923. However, wage payments were suspended for several months from the end of September 1923 during the peak phase of inflation. Presumably everyone was happy to have a roof over the heads and to be supplied with food from the farm. Wage payments were then resumed in January 1924 after the currency reform.

From the monthly expenses, it can be concluded that the farm already had an electricity connection at the end of 1921. This is shown by the expenses for light bulbs, that appear regularly. In general, Xaver Haslinger’s and his family seem to have been open to innovations. A milk centrifuge was in use on the farm. A washing machine was purchased for 220,000 Marks in February 1923. One year later, in February 1924, a flush toilet was installed on the farm. Bicycles were also in use. An engine was purchased for 205 marks in December 1926. Unfortunately, there is no further information about what type of engine it was.

Xaver was interested in improving the soil conditions. To do this, he had drainage laid and deliberately used lime and ammonia fertilizers. In the later 1920s, artificial fertilizers were also used.

Source for chapter (13)

Concluding remarks

The inhabitants of the estate “Zum Radler” were in the fortunate position of living on a mixed farm with a high degree of self-supply, which meant that the most basic necessities of daily life were secured even during the hyperinflation phase and little money had to be spent on food and housing. As owners of a productive asset, the farm owner and his family were in a comparatively good position. In addition, the owner of the farm was able to keep the business in a good financial position through far-sighted management.

On the other hand, it can be assumed that the owner’s family as well as servants and day labourers who were employed on the farm were also affected by the decline in the value of their reserves – usually savings at the time. However, there are no records of this in the budget book.

And today? In connection with the recent inflation situation, horror scenarios reminiscent of the situation in 1923 were sometimes published. If you look at the reasons for the current inflation situation, you see that it was primarily driven by the shortage of energy. This means that the current situation is structured differently – there is no combination of five to six main factors that led to the build-up of hyperinflation in 1923. Currently, inflation is driven by the shortage of goods. Seen in this light, it is absurd to use the term hyperinflation in the current situation. On the other hand, issuing bonds that are not backed by economic output should be handled with extreme caution. Even after 100 years, this should still be an important lesson for central banks from German history.

List of Sources:

- Herzog Heinrich des XIV von Niederbayern, Urbar, 1320: after source (2) page 101 line 4

- Reinhart, Herbert, Die Straßennamen des Marktes Rotthalmünster im Spiegel der Ortsgeschichte, editor: Markt Rotthalmünster

- Delvaux de Fenffe, Gregor: planet wissen – Weimarer Republik: Die Hyperinflation von 1923. Wer bezahlt den Krieg? (source available on 19/04/2013)

- Kunzel, Michael; Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin; 14. September 2014: Weimarer Republik – Innenpolitik – Die Inflation (source available on 23/07/2023)

- Kunzel (op. cit.): Die Inflation nach Kriegsende 1918; lines 19 – 21

- Kunzel (op. cit.): Die Hyperinflation 1923; lines 29 – 31

- Kunzel (op. cit.): Die sozialen und politischen Folgen der Inflation; line 21

- Kunzel (op. cit.): Die sozialen und politischen Folgen der Inflation; lines 23 – 26

- Kunzel (op. cit.): Die Währungsreform; line 21

- Ausgaben privater Haushalte für Obst und Gemüse erstmals höher als für Fleisch und Fisch (after Destatis, status on 13/12/2022; source available on 18/07/2023)

- Kunzel (op. cit.): Die Inflation nach Kriegsende 1918; from Graph: Inflation im Deutschen Reich 1919 – 1923

- Merl, Karin: Steueränderungen 2023: Das müssen Landwirte jetzt wissen und beachten (status on 20/02/2023; source available on 27/07/2023)

- Haslinger, Xaver: Haushaltsbuch, 1921 bis 1929

Sources of photos:

- Photos 01, 03, 04: Ziegler family archive, Weimörting, Rotthalmünster

- Photo 02: Photo author

- Photo 04: Haslinger, Xaver: budget book, 1921 to 1929

Author: Albert Kühnstetter (ÖLM) with the support of Hans Ziegler.